As the main candidates head to a runoff, disinformation is running riot on Turkish social media.

ON THE EVENING of Turkey’s most significant elections of the past two decades, Can Semercioğlu went to bed early. For the past seven years, Semercioğlu has worked for Teyit, the largest independent fact-checking group in Turkey, but that Sunday, May 14, was surprisingly one of the quietest nights he remembers at the organization.

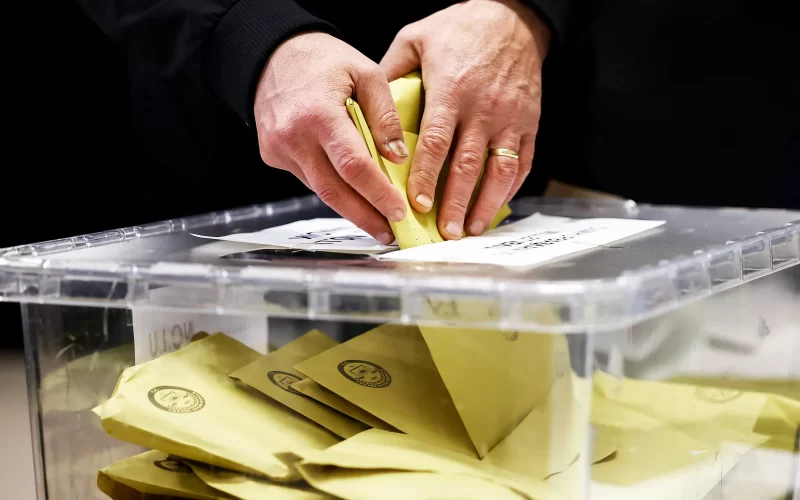

Before the vote, opinion polls had suggested that incumbent president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was losing support due to devastating earthquakes in southeastern Turkey that killed nearly 60,000 people and a struggling economy. However, he still managed to secure just under 50 percent of the vote. His main opponent, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, who heads the Millet Alliance group of opposition parties, received around 45 percent, meaning the two will face off in a second round scheduled for May 28.

“That night we didn’t have much work to do because people were talking about the results,” Semercioğlu says. “Opposition supporters were sad, Erdoğan supporters were happy, and that was what everybody was mostly discussing on social media.”

It was a rare moment of respite. The days leading up to the vote and afterward, as the runoff approaches, have been intense at Teyit, whose name translates into confirmation or verification. The morning after the election, reports of stolen votes, missing ballots, and other inconsistencies—most of which proved to be false or exaggerated—flooded social media. Semercioğlu says his colleagues’ working hours have doubled since early March, when Erdoğan announced the date for the election. This election cycle has been marred by a torrent of misinformation and disinformation on social media, made more difficult by a media environment that, after years of pressure from the government, has been accused of systematic bias toward the incumbent president. That has intensified as the Erdoğan administration struggles to hold onto power.

“We have been working 24/7 for a very long time. Misleading information about politicians’ backgrounds and statements was prevalent in these elections. We frequently encountered decontextualized statements, distortions, manipulation, and cheapfakes,” Semercioğlu says. But this wasn’t a surprise. And, he says. “We are seeing a similar flow in the second round.”

Fact checkers’ work has been complicated by the willingness of the candidates—from the government and the opposition—to use manipulated material in their campaigns. On May 1, a small Islamist news outlet, Yeni Akit, published a manipulated video purportedly showing the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)—an organization designated as a terrorist group by both Turkey and the US—endorsing Kılıçdaroğlu. On May 7, the same video was shown during one of Erdoğan’s campaign rallies.

“It was surprising that Erdoğan showed a manipulated video showing Millet Alliance candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu side by side with PKK militants at rallies. It was a clearly manipulated video, but it was widely spread and adopted by the public” says Semercioğlu, adding that although it was debunked by Teyit, “it was quite effective.”

The video was widely circulated and made its way into search results for the opposition candidate.

“When internet users turned to Google to search for Kılıçdaroğlu on that day, the false news was among the top suggestions made by the algorithm,” says Emre Kizilkaya, researcher and managing editor of Journo.com.tr, a nonprofit journalism website. Kizilkaya says his research has shown that Google results are a primary source of news for Turkish consumers, “who typically lack strong loyalty to particular news brands.” During the election run-up, he says Google results disproportionately favored media that was friendly to the president.

FEATURED VIDEOTheoretical Physicist Explains Time in 5 Levels of Difficulty

MOST POPULAR

- CULTUREThe Day Streaming DiedANGELA WATERCUTTER

- BUSINESSShocking Leaked Tesla Documents Hint at Cybertruck ProblemsCHRIS STOKEL-WALKER

- BUSINESSHumanoid Robots Are Coming of AgeWILL KNIGHT

- GEARThe Best Nintendo Switch Games for Every Kind of PlayerWIRED STAFF

Kizilkaya, who is also the vice chair of the Vienna-based NGO International Press Institute (IPI) and the chair of IPI’s National Committee in Turkey, believes government propagandists have been able to dominate social media platforms with their messaging. “Pro-government trolls and bots, employed in the thousands since 2013, bombarded social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok with the fabricated video, which consequently garnered tens of millions of views” he says.

A third presidential candidate, Muharrem İnce, withdrew from the race only days before the election after an alleged sex tape was released online. İnce says it was a deepfake, which used his face and footage taken from “an Israeli porn site.” İnce, a longtime member of the Republican People’s party (CHP), took to Twitter to accuse Russia of producing the video.

Erkan Saka, professor of journalism and media studies at Istanbul Bilgi University, says the power of trolls may be overstated. The mainstream press reaches a larger audience, and much of it is friendly to the president. “The whole media establishment is in fact using disinformation,” Saka says.

The government did pass a new disinformation law last year, but critics say it has largely been used to attack the political opposition. On February 28, journalist Sinan Aygül was arrested in December 2022 over a tweet containing allegations about a sexual abuse case involving a government employee. He later deleted the tweet and apologized, but he was sentenced to 10 months in prison. In the same month, Kurdish freelance journalist Mir Ali Kocer was detained on suspicion of spreading fake news while covering the aftermath of the earthquakes in southeast Turkey.

“I didn’t see any pro-government person persecuted through that law, but some critical journalists are already in prison because of it,” says Saka. “There are definitely double standards, and it is mostly against the opposition. Of course, there are cases of disinformation, but the way this is criminalized is very problematic.”

Turkey ranks 165 out of 180 countries on the Reporters Without Borders world press freedom index and has fallen 15 places since last year.

The Turkish government has also been accused of using its powers to skew debate on social media. The country has blocked Twitter several times, most recently last February. On the eve of the election in May, Twitter agreed to block several accounts at the request of the Turkish government. Elon Musk, who was then CEO, defended the decision, saying that if the company had not agreed to the request, all Turkish users could have lost access to the service—but his critics say the platform helped the government censor opposition voices.

Censorship, and the skewing of the media landscape toward pro-Erdoğan outlets, means Turkish voters have few trusted places to turn to for information. “There isn’t a reliable media ecosystem in Turkey, and unfortunately this causes disinformation,” Saka says. “People are looking for information, and when you can’t find a good source, you go to social media, and there you will probably be exposed to some kind of disinformation.”

MOST POPULAR

- CULTUREThe Day Streaming DiedANGELA WATERCUTTER

- BUSINESSShocking Leaked Tesla Documents Hint at Cybertruck ProblemsCHRIS STOKEL-WALKER

- BUSINESSHumanoid Robots Are Coming of AgeWILL KNIGHT

- GEARThe Best Nintendo Switch Games for Every Kind of PlayerWIRED STAFF

With the runoff approaching, both main candidates are focusing their attention on courting nationalist voters. Erdoğan’s campaign continues to link his opponent to the PKK, while Kılıçdaroğlu’s camp is pushing a narrative about large-scale migration into Turkey. “They allow the infiltration of 10 million refugees into Turkey. If they stay, the number will be up to 30 million and threaten our existence,” he said in a video posted to Twitter.

A lot of the campaigning has moved to TikTok, Saka says, which has “become a viral source of disinformation” in recent months. “I believe we will have a very ugly week,” he says. “Voters nowadays are more vulnerable than before.”

The sheer volume of dis- and misinformation is a challenge for small fact-checking outlets. Teyit has just 18 full-time fact checkers, and 20 freelancers. “Even if you build a team of thousands of people, it is hard to overcome all of it,” Semercioğlu says.

During the election period, they post around 200 analyses per month. They’ve built a “statement control” feature on top of their website, asking readers to help them identify false statements made by politicians. And they’ve added a button so users can request corrections from politicians who post misleading information on Twitter. A lot of people have pressed the button, but, Semercioğlu says with some disappointment, the results haven’t been encouraging. “We would have expected more politicians to take action to correct misleading information.”

Source: Wired