Nato has formally launched the process to bring Sweden and Finland into its military alliance. But a key condition for Nato member Turkey is the handover of more than 70 people described by its president as terrorists.

The leaders of the two Nordic nations say they are taking the issue seriously, but ultimately extradition is up to the courts not politicians. So who does Turkey want and could they ever be deported to Ankara?

Turkey’s demands

Sweden and Finland applied to join the West’s defensive alliance after Russia launched its war in Ukraine. Turkey was the only one of Nato’s 30 member states to block their bids until the two Nordic states agreed to a set of demands – including handing over individuals with alleged terror links.

https://emp.bbc.com/emp/SMPj/2.47.3/iframe.htmlMedia caption,

Watch: Handshakes as Turkey signs agreement to support Finland and Sweden joining Nato

Under a memorandum signed at a Nato summit last week, Finland and Sweden agreed to address Turkey’s “pending deportation or extradition requests of terror suspects expeditiously and thoroughly”, with “bilateral legal frameworks to facilitate extradition”.

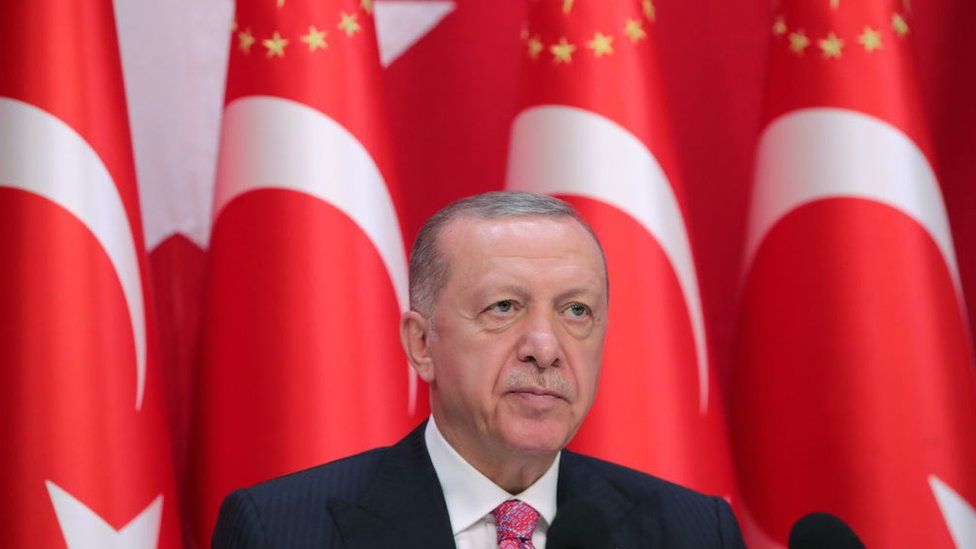

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said Sweden had promised to extradite 73 “terrorists” and had already sent three or four of them. Pro-government Turkish daily Hurriyet published a list of 45 people, including 33 sought from Sweden and 12 from Finland.

Sought by Turkey

Turkey is particularly keen on the handover of individuals it considers linked to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), considered a terror group by the EU, US and UK. It is also after followers of exiled Turkish cleric Fethullah Gulen. Gulenists are blamed by Turkey for a failed coup against President Erdogan in 2016.

The BBC has spoken to three of the people sought by Turkey.

Bulent Kenes: Journalist

For years, he was editor-in-chief of Today’s Zaman, a major English-language daily in Turkey, before it was shut down in 2016. Now, he lives in exile in Stockholm.

Turkish authorities accuse him of being part of the Gulen movement, or what they call the Fethullah Terrorist Organisation (Feto). It is known for its network of schools and is not considered a terror group in the EU, UK or US.

Mr Kenes said he became a target for his outspoken criticism of President Erdogan and faced accusations of plotting to topple the government: “All the allegations are fabricated. I am an independent journalist with no affiliations with any organisation.”

He was given a suspended jail term in 2015 for “insulting the president”, in a tweet that said Mr Erdogan’s late mother would be ashamed of him.

Insulting President Erdogan remains a common charge today, with 17 journalists and cartoonists put on trial in the first three months of 2022, according to independent Turkish organisation Bianet.

Bulent Kenes believes he has become a bargaining chip between Mr Erdogan and Sweden in Nato negotiations.

He is not particularly afraid of being extradited, as that would be a “betrayal of Sweden’s own values” of democracy and protecting dissidents. “This is not a test for the Erdogan regime… this is a test for the Swedish authorities,” he said.

Fatih: ‘Reformed arsonist’

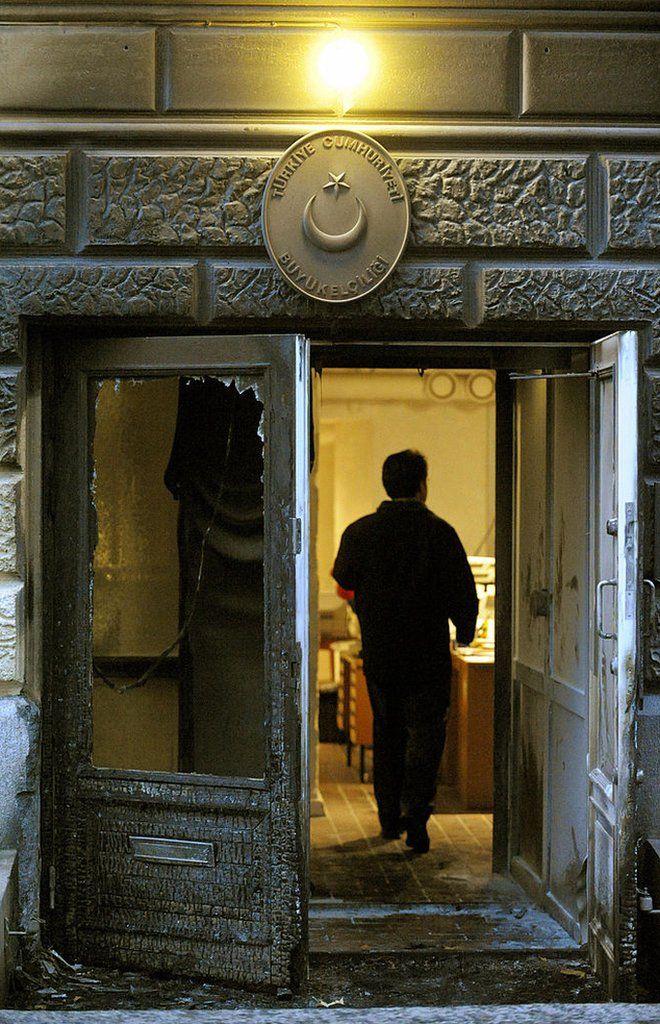

Others on Turkey’s list are far less prominent. Fatih, a Finnish Kurd, was part of a group of five young men who set fire to the door of the Turkish embassy in 2008.

Now a 37-year-old business owner and entrepreneur, he told the BBC he regretted what he did: “At that time, my life was messed up, I had many kinds of problems.”

He was surprised to find his name on the list as he finished serving a 14-month suspended sentence long ago – and paid damages to the embassy. Finnish authorities granted him citizenship a few years ago and considered the embassy case closed, he said.

Turkey accuses him of being a member of the militant PKK, which calls for greater Kurdish self-governance and is involved in an armed struggle with the Turkish state.

Fatih said he had no ties or ideological connections to the PKK, and believed he was targeted purely because of his Kurdish background.

Kurds make up 15-20% of Turkey’s population but have faced persecution in Turkey for generations. The government in Ankara is trying to ban the pro-Kurdish HDP party, the third biggest in parliament.

While Fatih did not believe he would be extradited as a Finnish citizen, he feared harassment in the local Turkish community or possible arrest abroad at Turkey’s request. He said he was very sad that Finland was having to “fight for him”.

Aysen Furhoff: Teacher who fled

Aysen Furhoff came to Sweden after serving five years of a life sentence in Turkey for trying to “subvert the constitutional order” when she was 17 and a member of the Turkish Communist Party. She said she was offered protection in Sweden after being tortured in jail.

Now 45, she lives in Stockholm with her husband and daughter and works as a teacher, and insists she is no longer involved in Turkish politics.

“I left Turkey 20 years ago. If I get sent there, they will have no use for me. Everyone I know is either dead or in prison. That’s why being on the list was surprising – who am I to them?”

Ms Furhoff says she is also being prosecuted in Turkey for being a PKK member. She admits collaborating with them for three months some 25 years ago.

While she no longer sympathises with the PKK, she denies they are a terror group and believes they should be part of discussions for a negotiated peace in Turkey.

Citing Swedish law, she is not worried about extradition but finds it hard to believe she could be an important case for Ankara.

Barriers to extradition

Legal requirements in Sweden and Finland make it very hard for Turkey to extradite the kind of numbers it wants:

- An independent court has the final say on extradition – not politicians

- Citizens of neither Sweden nor Finland can be extradited

- Foreign nationals can be extradited – but only if in line with the European Convention on Extradition

- Extradition is not allowed for political crimes or to countries where people risk persecution

- Alleged offences must be seen as a crime in Sweden or Finland.

According to Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter, of the 33 Swedish names listed in Turkish media, 19 have already been rejected for extradition by Stockholm’s Supreme Court.

“We cannot go through earlier cases that have already been processed,” said Chief Justice Anders Eka.

Finland has extradited two people to Turkey out of more than a dozen requests over the past decade. The justice ministry says no new requests have been received and it has promised the Kurdish community there will be no change to the law.

Possible backlash

If Turkey’s demands are rejected, it could withdraw its support for the Nordic nations’ accession to Nato, says Murat Yesiltas of pro-government think tank Seta.

Parliaments in all 30 Nato countries will need to approve Sweden and Finland as members and that includes Turkish lawmakers. So Mr Yesiltas warns it is also about the “dignity of the Turkish parliament”.

Other commentators suggest Ankara’s push for extradition may be an Erdogan re-election strategy, or a tool to help land a US weapons sale.

There is little chance of Sweden or Finland handing over anyone on the list any time soon.

One former PKK member on the list, Cemil Aygan, has been targeted for extradition by Turkey in the past but believes Sweden’s Supreme Court will stand in its way. “If Sweden were to hand me over, my life would be over,” he told public broadcaster SVT.

Source: BBC